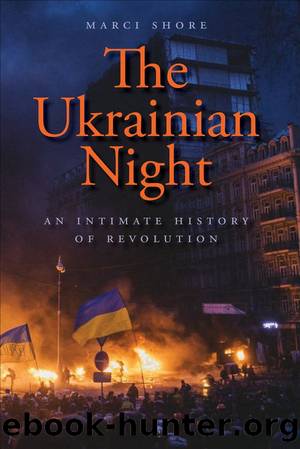

The Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution by Marci Shore

Author:Marci Shore

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2017-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

Putinâs Sirens

By spring 2014, Crimea was a fait accompli. On 25 May 2014, the same day as the European parliamentary elections, Ukraine held an election âbetween the Chocolate King and the Gas Princess.â The Chocolate King, Petro Poroshenko, won. The far Right got very little support: Oleh Tyahnybok, leader of Svoboda, and Dmytro Yarosh, leader of Pravyi Sektor, won just over and just under 1 percent of the vote, respectivelyâeach receiving fewer votes than Vadim Rabinovich, leader of the Ukrainian Jewish Congress. In the October 2014 parliamentary elections, neither Svoboda nor Pravyi Sektor reached the 5 percent threshold needed to enter parliament. This was in contrast to the far-Right Freiheitliche Partei Ãsterreichs, which won close to 20 percent of the Austrian vote in the European parliamentary elections, and Marine Le Penâs far-Right Front National in France, which won close to 25 percent. It was as if Freudâs ghost were haunting Europe, and Austria and France were gazing at Ukraine through the lens of projection, attributing to others what they could not accept in themselves.

Europeans preferred to put Crimea out of their minds. No one in Brussels wanted to go to war against Russia. The passive condoning of Putinâs annexation of the Black Sea peninsula was reminiscent of Neville Chamberlainâs âappeasement at Munich,â Western Europeâs acquiescence to Hitlerâs annexation of the Sudetenland. Everyone began asking the same question: âWhat will Putin do? What are Putinâs plans? What is Putin thinking?â It was as if there were an unspoken understanding that, once again, the fate of Europe lay in one manâs mind.

âHeâs living in a different world,â German chancellor Angela Merkel said after she had spoken by phone to Putin at the very beginning of March. Unlike her predecessor as chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, who traveled to Saint Petersburg in April 2014 to celebrate his seventieth birthday with Putin, Merkel was not enchanted with the Russian dictator. She was sober, and cautious. Merkel was a crisis manager, not a Putin sympathizerâin contrast to many of her fellow Germans, including those on both the far Right and the far Left. Putinâs defenders and apologists became known as âPutin-Versteherâ: those who âunderstoodâ Putin. Many of Ukraineâs leading writers and intellectuals were Germanists by education; they translated German literature, they lectured in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. This made the âPutin-Versteherâ phenomenon all the more painful to them.

Some explained Europeansâ Russian sympathies by crude financial interests: Russian oligarchs tended to keep their money in Europe; Austrian banks were especially desirable. Gerhard Schröder was chairman of the shareholdersâ committee of Putin-controlled Gazprom, the largest natural gas company in the world. In 2004, Schröder and his fourth wife adopted a three-year-old girl from a Russian orphanage. The legality of the adoption was murky: the child appeared to be a diplomatic giftâthat is, a human bribe. Others explained Putinâs attraction as that of a homoerotic Männerfreundschaft, a masculinizing ideal of men bonding while drinking vodka in forest lodges and hunting wild boar bare-chested on horseback. Still others explained this by German feelings of guilt towards Russia.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Third Pole by Mark Synnott(684)

Money for Nothing by Thomas Levenson(632)

Christian Ethics by Wilkens Steve;(576)

The Economist (20210109) by calibre(574)

Made in China by Anna Qu(546)

100 Posters That Changed The World by Salter Colin T.;(502)

Reopening Muslim Minds by Mustafa Akyol(494)

Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India by Knut A. Jacobsen(481)

The Irish Buddhist by Alicia Turner(480)

Nonstate Warfare by Stephen Biddle(472)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(465)

The Age of Louis XIV: The Story of Civilization by Will Durant(458)

The Great Pyramid Void Enigma by Scott Creighton(456)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(444)

The Shortest History of China by Linda Jaivin(439)

Banaras: CITY OF LIGHT by Diana L. Eck(431)

Objects of Vision by Saab A. Joan;(430)

The Jews of Silence: A Personal Report on Soviet Jewry by Elie Wiesel(428)

Sybille Bedford by Selina Hastings(418)